Arts & Culture October 2019

Northern Berkshires’ blue-collar lament

Professor’s book tracks region’s labor history, industrial decline

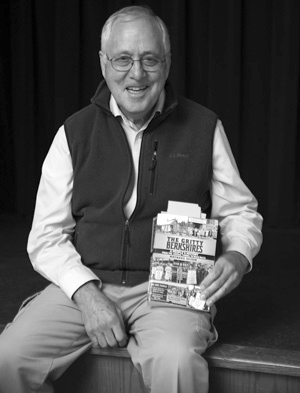

Maynard Seider, professor emeritus of sociology at the Massachusetts College of Liberals Arts, views the history of northern Berkshires through a labor lens in his new book, “The Gritty Berkshires.” Susan Sabino photo

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

When Maynard Seider arrived in the northern Berkshires in 1977, he had no idea it would open up his life’s work and culminate in his new book, “The Gritty Berkshires: A People’s History from the Hoosac Tunnel to Mass MoCA.” The book recounts the history of North Adams, as well as Adams and Williamstown, through a labor lens, documenting the region’s working class.

That first visit to the Berkshires was for a job interview at North Adams State College – now the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts – for a position teaching sociology.

Seider is a Connecticut native, raised in a pro-union family and with a background in labor activism. He spent a year in California in the 1970s working in a factory when he was unable to find a job after completing his doctorate. That experience was the basis for his book “A Year in the Life of a Factory.”

“One of the things that I’ve always wanted to do is to bring out what ‘ordinary people’ were doing that often gets pushed aside, let’s say by the media,” Seider said, “and also gets forgotten because for people, time passes, and also some of it may get repressed.”

In many ways, Seider began gathering material for “The Gritty Berkshires” in his early days teaching in North Adams – and kept gathering for the next four decades.

In 1984, he devised a course covering the area’s labor history in honor of the 50th anniversary of the New Deal. That blossomed into a research class that Seider taught for 32 years.

Seider worked with students to compile oral histories that were part of their class requirements, pouring through newspaper archives and town records to uncover a forgotten labor history. At one point he and his students collaborated with former local labor leader Rene Ouellette, who led a strike at the sprawling Greylock Mill in the 1930s.

Seider’s mission gained further resources in the late 1980s when a statewide program, The Shifting Gears Project, hired professional historians to go to the state’s heritage parks and compile oral histories of how industrial cities had changed over time. Seider was able to pull from these histories, as well as industrial histories compiled by Williams College students, for his own work.

Tracking a city’s changes

Seider’s research led to a local history play that Seider produced at the college in 1995. Called “The Sprague Years” after the Sprague Electric Co. plant that once dominated the city’s economy, it featured actors whose performances were based on adapted transcripts of interviews as well as actual minutes from union meetings during the times the play portrayed. Local audiences who attended that week got to see actors portraying their parents and grandparents on stage.

In 2012, Seider produced the documentary “A Farewell To Factory Towns,” which focused on North Adams and the closing of Sprague Electric in the context of the wider course of deindustrialization in America.

But if the closing of Sprague in the 1980s is the pivotal event in modern North Adams history, and the one that has provided the starting point for its new identity as an arts town, Seider considers the Sprague strike in 1970 as the important precursor to plant’s closing. The strike, he says, set the tone for the city’s psychology when industry began to move away. Prior to the 1970s, unions in North Adams were fairly isolated from the outside world, operating on their own terms.

“In many cases, they were local unions; they weren’t part of national unions,” Seider said. “I think there was a certain amount of maybe cynicism about outsiders coming in and trying to organize, like ‘We can do it ourselves.’ So in a sense that gave people here a certain amount of strength because they were able to do it themselves, but it also meant that they didn’t necessarily have access to help that would be useful from the outside.”

By the late 1960s, that situation began to change, and outside organizations become involved in contract talks at Sprague. Demanding a living wage, the workers called the strike on March 1, 1970, amidst fear mongering that it would cause Sprague to relocate. The strike ended after 10 weeks, delivering an agreeable win for the workers, though costing some jobs.

By 1976, Sprague was purchased by GK Technologies, which made record profits before being bought by Penn Central Corp. in 1981.

“I remember when Penn Central bought it,” Seider said. “By that time it was already out of the control of the Sprague family, and Penn Central calls the news conference and John Sprague. Sprague announced that they were going to move corporate headquarters closer to Boston, and he had all kinds of reasons for doing so. And he tried to basically tell people, ‘Don’t worry about it. We’re only talking about maybe a dozen positions. Manufacturing’s going to stay in North Adams.’

“But I think most people were really, really worried about that,” Seider recalled. “Sprague basically closed for all intents and purposes, with some exceptions, around ‘85, ‘86.”

De-industrialization, Seider points out, was just in the air in the United States at the time, and what happened was not entirely unexpected. But it still was a big psychological blow to North Adams. And guided by revisionist voices, he said, some of the workers blamed themselves. Looking back to the 1970 strike, they expressed concern that their actions had led to Sprague’s departure and decided they never should have gone on strike.

That’s when Seider began to look at the question of memory and how it affects labor action, as well as the morale of the work force. He wanted to find out what people remember and why they remember it.

“There’s kind of lived history -- and then there’s memory of history,” Seider said. “That’s part of what I wanted to bring out. I wanted to show that in fact, people were not passive earlier on, that they did in fact make demands. They did in fact organize. It wasn’t like everything was quiet and then 1970 came and everything changed.”

From industry to the arts

Seider’s book documents exactly what he set out to reveal as it moves from Chinese laborers in shoe manufacturing and the dangerous construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in the 19th century to the 1980s case of X-Tyal, which inspired activism like North Adams had never witnessed, covering numerous labor disputes and working-class issues in between.

But the book also moves into the present, giving coverage to labor disasters like the closing of the North Adams Regional Hospital, which Seider sees as a symbol of how the economic concerns of the city have shifted -- and not in favor of the working class. It’s a dynamic that reflects the labor battles of old, but without a union buffering against management.

“I’ve been very disappointed by elected officials ignoring it and saying, ‘Well look, this is what we have, and this is fine, and let’s not talk about the past, let’s move to the future,’” Seider said. “In 2014, the same time the hospital was closing, the Legislature granted over $24 million for MoCA to renovate for Building 6. I mean you might say it’s coincidental, but it also says something about what the priorities were.”

Seider winds down his book by examining the big changes in the way the economy is approached in North Adams, most specifically through the creation and expansion of Mass MoCA in the former Sprague Electric complex. The shift to an arts- and tourism-based economy has inspired further development like the announced plans of Mass MoCA creator Thomas Krens’ total makeover of the city, built around a model train museum.

In this way, Seider laments the advent of trickle-down economics and the passing of the days when the labor movement had a vigorous say in the direction of North Adams.

“When people want to talk about economic development, they tend to talk about some savior coming in -- whether it’s a sports stadium, whether it’s a casino, whether it’s a museum -- and somehow those people on the very top will prosper in one way or another and it will help everybody,” Seider said. “It will help everybody else. There’s no direct way of helping working-class people.”

Maynard Seider will be giving readings from “The Gritty Berkshires” at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 15, at the Lanesborough Public Library, at 83 North Main St. in Lanesborough, and at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 17, at North Adams Public Library, at 74 Church St. in North Adams.

Visit www.thegrittyberkshires.com for more information about the book.

Visit archive.org/details/77981FarewellFactoryTowns to view Seider’s documentary “Farewell to Factory Towns.”